Melissa Smith has spent three decades working on health and social justice in communities in the US and abroad. Now she is continuing her life’s work at UC Santa Barbara (UCSB) and with the UCGHI Women’s Health, Gender and Empowerment Center of Expertise (WHGE COE).

Last summer Smith and her husband, Charlie Hale, now Dean of Social Sciences at UCSB, moved from Austin, Texas to Santa Barbara. She serves as the director of Health Equity Initiatives at UCSB, where she co-teaches a seminar on community-based participatory research on health disparities, and is the director of education and training for the UCGHI Women’s Health, Gender and Empowerment Center of Expertise. She is also leading the Global Health in Mexico program with UC Education Abroad this summer.

“My goal is, and always has been, to advance collaborative work between academic and community partners, in an effort to foster the conditions that can achieve health equity for all,” said Smith.

During her second year of college – while grappling with the decision to become a doctor, a midwife, or work in public health – Smith sought out a direct life experience that would help clarify her path. At 20 years old, she took a position at a rural clinic in Liberia and spent a year as a volunteer community health worker. It was during this time that she had a defining experience.

Smith was involved in caring for a one-year-old girl who suffered from malnutrition, diarrhea and dehydration. “There was a lot of conflict between [the girl’s] mother, who believed in traditional medicine, and the Western-trained Liberian nurse. Because of complex barriers, particularly the nurses’ lack of cultural humility, the girl’s mother did not trust the health system, and the baby ended up dying in my arms,” said Smith.

In that moment, Smith knew she wanted to become a physician so she could offer tangible skills to poor communities. “It also made me want to work directly with communities on the root causes of the health problems they face,” said Smith.

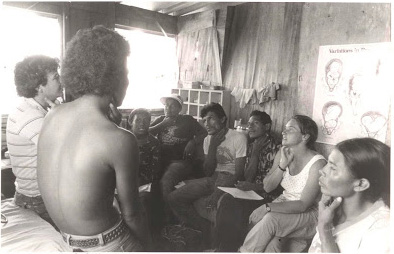

Smith studied medicine at the University of Washington and in her last year of medical school, took a year’s leave to work with the Nicaraguan Ministry of Health’s Department of Popular Health Education. “There was a socialist revolution underway at the time, with strong government support focused on the social determinants of health, and for training community health workers and midwives,” recalled Smith.

She returned to Seattle for her residency in family medicine before moving to Northern California where she worked in migrant worker clinics. However, it was not long until Hale's work as an anthropologist, and hers as a physician and trainer, brought her back to Latin America, this time to spend a year with their two young daughters in Guatemala.

Smith provided women’s health care in a local clinic, as well as worked with the Association of Community Health Services, (ASECSA), a Guatemalan organization that trains midwives and community health workers in the indigenous communities of the highlands of Guatemala. Meanwhile she also served as medical editor and field-tester for a book titled Where Women Have No Doctor, a health resource developed by Hesperian Health Guides, a nonprofit organization that supports individuals and communities in their struggles to realize the right to health.

While in Liberia, Smith had used Hesperian’s well-known resource Where There Is No Doctor, and while in Nicaragua, she had used their book Helping Health Workers Learn. “I knew these resources well, and the positive impact they can have on communities,” said Smith.

“While the Guatemalan women greatly appreciated Where Women Have No Doctor, they wanted to know more than how to solve women’s health problems; they wanted to know how to raise awareness that the lives and health of women and girls matter. They asked for information about how to advocate for the health and rights of women and girls in their community,” explained Smith. This planted the seed for a companion book to Where Women Have No Doctor titled Health Actions for Women; Practical Strategies to Mobilize for Change – funding for which would not exist until years later.

Austin, Texas, 2006.

With Where Women Have No Doctor completed and published, Smith, Hale and children had meanwhile relocated to Austin, Texas, where they stayed for twenty years. She worked in a clinic for the working poor and uninsured, many of whom were undocumented immigrants from Mexico and Central America. Smith dove into a variety of health and social justice efforts in Austin, including co-developing a program on community-based participatory research on health at the University of Texas.

In 2007, Smith and her colleagues at Hesperian Health Guides received funding: the Health Actions for Women project was a go. Twelve years after the concept was imagined in Guatemala, the project could be realized. Smith, her Hesperian colleagues, and partners around the world jumped into making this idea a reality.

The process included collaboration with a steering group of women from every continent as well as with 41 grassroots groups in 23 countries, collecting ideas, experiences and strategies, and field-testing content and training activities, according to Smith. The best approaches to advocating for the health and rights of women and girls make up the pages of Health Actions for Women, published in 2015, available on Hesperian’s open-source digital platform, and now translated into seven languages, with more translations underway.

“I feel deeply gratified and privileged to be part of a process that found a way to affirm the ideas and experiences of grassroots women throughout the world and have their wisdom and insight inform this resource,” said Smith.

Reflecting on her career, Smith expressed gratitude for being able to work with poor communities in the US as well as in Latin America for the right to health. “The lessons learned in these experiences guide my approach in collaborative efforts to advance global health equity.”