Working Globally, Locally: GloCal Fellow Manages Tanzanian Project from California

Without the COVID-19 pandemic, GloCal fellow Dr. Abigail Cortez would be in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, working side-by-side with her Tanzanian partners at the Muhimbili Orthopedic Institute. Instead, by communicating regularly virtually with her mentors and a team of Tanzanian clinicians and research coordinators, she’s successfully managing her GloCal research project from her home in California.

“Obviously, it would be much easier if I was on-site and able to see patients myself and work with the coordinators on making sure all the data’s clean and accurate,” she said.

But working remotely “works out pretty well because we’re in constant communication,” she said. “I feel very comfortable with where the progress is because I have a lot of supervision from my mentors and the research coordinators in Tanzania are very responsive,” to her email messages and WhatsApp messages, she said.

Cortez, an orthopedic surgery resident at the University of California, Los Angeles, is studying how to improve trauma care in low- and middle-income countries. Her project is a follow-up to a previous study conducted by her University of California, San Francisco, mentor, Dr. Saam Morshed, on two forms of treatment for open tibia fractures: “basically, when your shinbone breaks and the bone pokes through the skin,” she said. In these countries, such fractures are commonly caused by road traffic accidents.

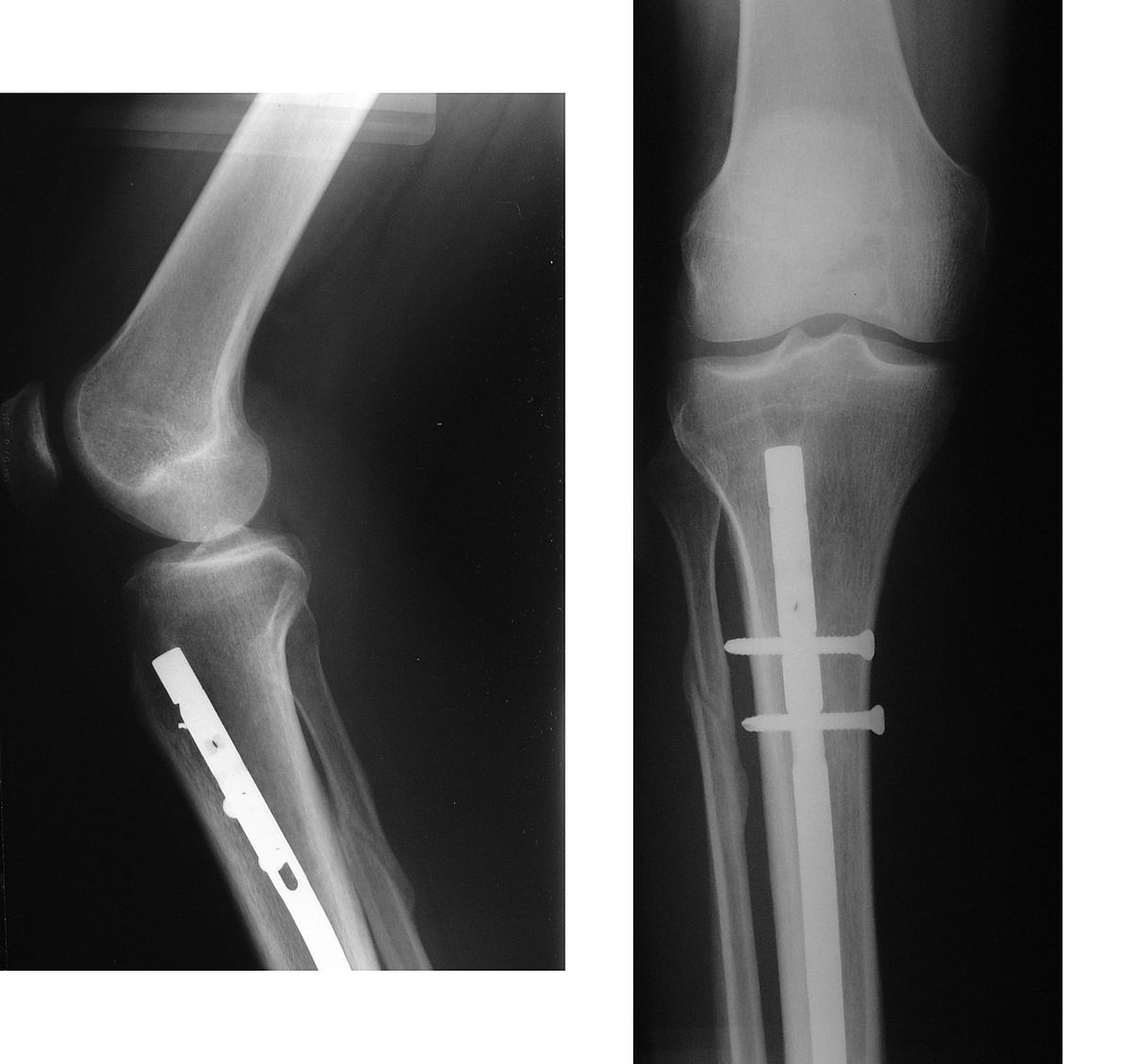

The previous study was a randomized controlled trial to assess outcomes of two methods of fracture repair—external fixation versus intramedullary nail fixation. In external fixation, a series of rods and pins stabilizes the bone fragments outside the skin. With intramedullary nail fixation, a long nail is placed inside the bone to stabilize the fracture internally.

Intramedullary nail fixation is commonly used in high-income countries for open tibia repair. One of the advantages of intramedullary nailing is a shorter recovery time as patients can bear weight on the injured leg much sooner after surgery. But how successful this surgery would be in a lower middle-income country like Tanzania where the supplies, training, and equipment needed to insert the nail are limited wasn’t known.

The initial study found no differences in complications requiring reoperation one year after surgery. Cortez’s project includes patients from the original study several years after their surgeries to understand any post-surgery challenges, long-term issues with the methods, and whether intramedullary nail fixation offered the patients an overall better experience.

“Musculoskeletal trauma is a huge source of morbidity and mortality in low- and middle-income countries,” Cortez said. “We're focusing on how to optimize care for these injuries because trauma care isn't really optimized in these countries. We're trying to do our part in contributing the research in our field.”

The project is nearing the end of the enrollment phase with more than 100 of the original patients participating, Cortez said. Those willing to come into a clinic offering Saturday hours answer a questionnaire given by clinic staff and have a physical examination and X-rays taken. Those unwilling or unable to come in answer the questions by telephone. The questions are designed to gather information about complications, such as reoperations for fracture-related infections, bones failing to heal, or malalignment, and about the patients’ quality of life.

A problem with external fixation is that patients can’t put weight on the broken leg for several weeks. This keeps them from quickly resuming their normal routines, and could lead to financial and social hardships for them. The questionnaire includes queries about whether patients were working for pay before their injury, whether they are currently working for pay, how many months after their injury they returned to work, and whether they've borrowed money from anyone in their household or had to sell any assets because of the injury.

To ensure the project moves forward despite her not being physically present, Cortez meets virtually with her mentors in the United States, Dr. Morshed and Dr. David Shearer, every week. She also meets once to twice per month with her Tanzanian mentor, Dr. Billy Haonga, and the project’s research coordinators and contacts the coordinators outside of the meetings.

The regular contact has helped the team identify and solve problems. For example, early in the fellowship year Cortez and her mentors saw a drop in entries in the project database for patient information. During a meeting with the local research coordinators, the team learned that many cell phone SIM cards in Tanzania had been switched off because they weren't properly registered with the government.

The team developed a list of patients who hadn’t been reached and asked the coordinators to periodically call the numbers over several months. The coordinators were able to contact and get information from several patients whose numbers were eventually reconnected.

While Cortez would have appreciated the opportunity to work on-site internationally, she feels the experience she’s gained from the fellowship will help her reach her long-term goal: becoming a clinical scientist in global orthopedics. Cortez, who is ethnically Filipino, hopes to eventually work in Southeast Asia, particularly the Philippines.

Starting effective global health research projects is “about finding the right people,” she said. “I think it'll be pretty easy to find projects now that I'm in this network” through the fellowship, she said.